Could Eating the Right Fats Save 1 Million Lives per Year?

by Dr. Mercola

You know the drill. Watch or read the health media and you will be regularly told to avoid saturated fats because they raise your LDL cholesterol, which will ultimately clog your arteries and lead to heart disease.

The problem with this recommendation is that it is only based on a theory, and worse yet that theory has never been proven. In fact, the recent studies that carefully examine saturated fat disprove this.

The video above provides a comical illustration of what happens when a renowned international cardiologist publishes a groundbreaking article1 that debunks saturated fat. He is challenged by two ignorant dietitians spouting what they had been taught years ago.

Interestingly, a new American Heart Association (AHA) study claims eating the “right” fats could save 1 million lives per year.

Indeed, this is likely an understatement, but the researchers got the fats wrong and now are spreading misinformation that will likely cause needless pain, suffering and premature deaths.

Saturated Fats Are NOT to Blame for Heart Disease

The widely circulated assumption that eating a diet high in saturated fats leads to heart disease is simply wrong, as they are actually necessary to promote health and prevent disease. Dietary fats can be generally classified as:

- Saturated

- Monounsaturated

- Polyunsaturated

A “saturated” fat means that all carbon atoms have maxed out their hydrogens and as a result there are no double bonds that are perishable to oxidation and going rancid. Fats in foods contain a mixture of fats, but in foods of animal origin a large proportion of the fatty acids are saturated.

So How Did These Natural Saturated Fats Come to Be Vilified?

In 1953, Ancel Keys, Ph.D. published a seminal paper that led to a later study that served as the basis for nearly all of the initial scientific support for the so-called “diet-heart hypothesis.”

Conducted from 1958 to 1970, and known as the Seven Countries Study, this research linked the consumption of dietary fat to coronary heart disease.2

What you may not know is that when Keys published his analysis that claimed to prove the link between dietary fats and heart disease, he selectively analyzed information from only seven countries to prove his correlation, rather than comparing all the data available at the time — from 22 countries.

As you might suspect, the studies he excluded were those that did not fit with his hypothesis, namely those that showed a low percentage of fat in their diet and a high incidence of death from heart disease as well as those with a high-fat diet and low incidence of heart disease (like France).

If all 22 countries had been analyzed, there would have been no correlation found whatsoever.

Journalist Nina Teicholz, author of “The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet,” also stated that when researchers went back and analyzed some of the original data, heart disease was most correlated with sugar intake, not saturated fat.3

What’s Wrong With the 2015 Dietary Guidelines?

I recently interviewed Nina Teicholz about the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (below). While there were many positive changes, such as the elimination of a limit on dietary cholesterol, the fallacies about saturated fats remain.

These guidelines are highly relevant, as they determine what foods will be served in feeding assistance programs, including the National School Lunch Program, programs for the elderly, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and military rations.

Through these programs, they determine what 1 in 4 Americans will eat on a daily basis. They also dictate the advice you’ll get from your doctor, nutritionist, or dietician. According to Nina, when the guidelines were launched in the 1980’s, one single Senate staffer wrote what became the national dietary guideline.

He was heavily influenced by certain scientists, and didn’t have the background to conduct a sound review of the science.

Those guidelines resulted in a diet that is low in fat and high in carbohydrates, and it has remained that way ever since. This type of diet is clearly tied to obesity, diabetes, and many other chronic health problems.

The guidelines are still to this day heavily influenced by industries whose main concern is unrelated to the public health—a fact pointed out in Nina’s controversial article4 in The British Medical Journal, which was eventually retracted after 170 scientists signed a letter asking for its retraction.

Why The Saturated Fat Myth Continues

Click HERE to watch the full interview!

So why does the saturated fat myth remain, despite all the evidence showing it’s false? Why won’t the guidelines committee review the now overwhelming evidence and set the record straight? As noted by Nina:

“I think that there are two kind of big explanations for why this is [not done]. One is that there are huge industry interests. Because the guidelines are part of the USDA, half of the USDA’s mission is to promote agriculture.

At the same time, they have a mandate to tell people to eat less of some things over other things. Those two mandates conflict…What are the industries that benefit from the guidelines? The makers of carbohydrate-based food… Corn, soy, and the vegetable oil manufacturers. Because when you tell people not to eat saturated fats, what they eat instead are unsaturated fats, mainly vegetable oils, which have increased over 91 percent over the last three decades…

The other major factor that keeps the guidelines from changing…is that there’s a tremendous professional investment in this particular kind of advice. There are university professors’ reputations staked on it. There are many institutions who have invested in this particular hypothesis about what makes people healthy… These giant institutions cannot be seen as flip-flopping. They can’t be wrong. That prevents backing out of any advice that might be flawed.”

Cutting Back on Saturated Fats Doesn’t Lengthen Life: 6 Major Studies

Six major clinical trials on saturated fat follow, many of which have been used to support the assumption that saturated fats cause heart disease. In reality, however, none of them showed that eating fewer saturated fats would both prevent heart disease and lengthen your life.

Together, they include more than 75,600 people in experiments lasting 1 to 12 years. All of these studies used “hard endpoints,” which are considered the most reliable measurements. The benefits for cardiovascular mortality and risk-factor reduction were mixed, but none of these trials showed that restricting saturated fats reduced total mortality.

- The Oslo Study (1968): A study of 412 men, aged 30 to 64 years, found eating a diet low in saturated fats and high in polyunsaturated fats had no influence on rates of sudden death.5

- L.A. Veterans Study (1969): A study of 850 elderly men that lasted for six years and is widely used to support the diet-heart hypothesis.

No significant difference was found in rates of sudden death or heart attack among men eating a mostly animal-foods diet and those eating a high-vegetable-oil diet. However, more non-cardiac deaths, including from cancer, were seen in the vegetable-oil group.6

- Minnesota Coronary Survey (began 1968, results delayed until 1989): A study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and involving more than 9,000 people. After 4.5 years, eating a low saturated fat, high-PUFA diet led to no reduction in cardiovascular events, cardiovascular deaths or total deaths.7

- The Finnish Mental Hospital Study (1968): A study of approximately 4,000 people followed for 12 years that is also widely cited in support of the diet-heart hypothesis. There was a reduction in heart disease among men following a low saturated fat, high-PUFA diet, but no significant reduction was seen among women.8

- London Soybean Oil Trial (1968): A study of nearly 400 men that lasted for two to seven years. No difference in heart attack rate was found between men following a diet low in saturated fats and high in soybean oil and those following an ordinary diet.9

- The U.S. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT): Sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, this is another study that is highly misleading.

It compared mortality rates and eating habits of over 12,000 men, and the finding that was widely publicized was that people who ate a low saturated fat and low-cholesterol diet had a marginal reduction in coronary heart disease. However, their mortality from all causes was higher.10

Saturated Fats Increase Large, Fluffy LDL Cholesterol — And That’s a Good Thing

In another comical video above, you find an overweight unhealthy dietitian (who appears like she is a heart attack waiting to happen) seeking to demonize saturated fat because of incorrect fatally flawed information she was previously taught.

As the above video clearly illustrates, there is a load of confusion and misinformation in the media even when seeking to present the truth. Part of the confusion is related to saturated fat’s impact on LDL cholesterol, often referred to as “bad” cholesterol.

First of all, all cholesterol is actually the same. When you hear terms like LDL and HDL, they’re referring to lipoproteins, which are proteins that carry cholesterol. LDL stands for low-density lipoprotein while HDL stands for high-density lipoprotein.

HDL cholesterol is actually linked to a lower risk of heart disease, which is why measurements of total cholesterol are useless when it comes to measuring such risk (if your total cholesterol is “high” because you have a lot of HDL, it’s no indication of increased heart risks; rather, it’s likely protective).

Saturated fats have been shown to actually raise protective HDL cholesterol — a benefit — and may also increase LDL. The latter isn’t necessarily bad either once you understand that there are different types of LDL.

- Small, dense LDL cholesterol

- Large, “fluffy” LDL cholesterol

Research has confirmed that large, fluffy LDL particles do not contribute to heart disease. The small, dense LDL particles, however, are easily oxidized, which may trigger heart disease. This is because the small, dense LDL penetrates your arterial wall more easily, and so they do contribute to the build-up of plaque in your arteries. Synthetic trans fat also increases small, dense LDL. Saturated fat, on the other hand, increases large, fluffy, — and benign — LDL.

Avoiding Saturated Fats May Lead to Poor Health

People with high levels of small, dense LDL have triple the risk of heart disease as people with high levels of large, fluffy LDL.11 And here’s another fact that might blow your mind: eating saturated fat may change the small, dense LDL in your body into the healthier large, fluffy LDL!12,13

Also important, research has shown that small, dense LDL particles are increased by eating refined sugar and carbohydrates, such as bread, bagels and soda.14 Together, trans fats and refined carbs do far more harm to your body than saturated fat ever could.

Unfortunately, when the diet-heart hypothesis took hold, the food industry switched over to low-fat foods, replacing healthy saturated fats like butter and lard with harmful trans fats (hydrogenated vegetables oils, margarine, etc.), and lots of refined sugar and processed fructose. Ever-rising obesity and heart disease rates clearly illustrate the ramifications of this flawed approach.

In 2013, an editorial in the British Medical Journal also described how the avoidance of saturated fat actually promotes poor health in a number of ways, including through their association with LDL cholesterol.15 As stated by the author Dr. Aseem Malhotra (featured in the videos above), an interventional cardiology specialist registrar at Croydon University Hospital in London:

“The mantra that saturated fat must be removed to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease has dominated dietary advice and guidelines for almost four decades. Yet scientific evidence shows that this advice has, paradoxically, increased our cardiovascular risk …

The aspect of dietary saturated fat that is believed to have the greatest influence on cardiovascular risk is elevated concentrations of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.

Yet the reduction in LDL cholesterol from reducing saturated fat intake seems to be specific to large, buoyant (type A) LDL particles, when in fact it is the small, dense (type B) particles (responsive to carbohydrate intake) that are implicated in cardiovascular disease.

Indeed, recent prospective cohort studies have not supported any significant association between saturated fat intake and cardiovascular risk Instead, saturated fat has been found to be protective.”

Dietary Guidelines to Reduce Fat Were Introduced Without Any Supporting Evidence

In 1977, the U.S. released the first national dietary guidelines, which urged Americans to cut back on fat intake. In a radical departure from current diets at the time, the guidelines suggested Americans eat a diet high in grains and low in fat, with vegetables oils taking the place of most animal fats. The U.K. released similar guidelines in 1983. The guidelines were controversial, and even the American Medical Association said at the time:16

“The evidence for assuming that benefits to be derived from the adoption of such universal dietary goals … is not conclusive and there is potential for harmful effects from a radical long-term dietary change as would occur through adoption of the proposed national goals.”

There’s no telling how many have been prematurely killed by following these flawed low-fat guidelines, yet despite mounting research refuting the value of cutting out fats, such recommendations are still being pushed. Further, according to research by Zoe Harcombe, Ph.D. and published in the Open Heart journal, there was no scientific basis for the recommendations to cut fat from the U.S. diet in the first place.17

The guidelines were, and still are, quite extreme, calling for Americans to reduce overall fat consumption to 30 percent of total energy intake and reduce saturated fat consumption to 10 percent of total energy intake. No randomized controlled trial (RCT) had tested these recommendations before their introduction, so Harcombe and colleagues examined the evidence from RCTs available to the U.S. and UK regulatory committees at the time the guidelines were implemented.

Six dietary trials, involving 2,467 men, were available, but there were no differences in all-cause mortality and only non-significant differences in heart-disease mortality resulting from the dietary interventions. As noted in Open Heart:18

“Recommendations were made for 276 million people following secondary studies of 2467 males, which reported identical all-cause mortality. RCT evidence did not support the introduction of dietary fat guidelines.”

Reducing Dietary Fat Experiment Has Been a Miserable Failure

In the decades following the release of the dietary guidelines, Americans followed suit, reducing their intake of animal fats and largely replacing them with grains, sugars and industrially processed vegetable oils. Yet, despite adherence to these supposedly “healthy” guidelines, U.S. public health declined. As noted by the Weston A. Price Foundation:

“Despite the lack of government guidance on how to prevent chronic disease through nutrition, heart disease rates had been decreasing in America since 1968, and in 1975, less than 15 percent of the population was considered obese.

In many regards, the health of Americans in the 1970s had never been better … trends indicate that, since 1980, the rates of many chronic diseases have increased dramatically. Prevalence of heart failure and stroke has increased significantly. Rates of new cases of all cancers have gone up.

Rates of diabetes have tripled. In addition, although body weight is not in itself a measure of health, as the 2000 DGAC [Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee] noted, rates of overweight and obesity have increased as Americans have adopted the eating patterns recommend by the DGA [Dietary Guidelines for Americans].”

This is not at all a surprising result, and actually what one would predict once they understand mitochondrial metabolism, which is designed to run far more efficiently on fats than glucose. Burning sugar as a primary fuel generates far more reactive oxygen species than fat and causes more free radicals and secondary tissue, protein and genetic damage.

This does not mean that we don’t need a healthy supply of carbs; they just need to be dwarfed by a much larger supply of healthy fats. As Dr. Ron Rosedale taught me, how long you live will in large part be determined by how much fat you burn relative to how much sugar.

Health Disaster: Study Suggests Americans Reduce Saturated Fats and Increase Vegetable Oils

The AHA has long promoted getting at least 5 percent to 10 percent of your daily energy requirement from omega-6 fats and teaches that reducing omega-6 polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) from current intake levels would likely increase your risk for coronary heart disease.

The new study, which was published on behalf of the American Heart Association, echoed this advice and suggested Americans not only reduce healthy saturated fats in their diet but also increase PUFAs.19

The study claims that about 10 percent of heart disease deaths, or 700,000 worldwide each year, are the result of eating not enough PUFAs as a replacement for saturated fats. The study’s senior author, Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, dean of the Tufts Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy in Boston, actually went on record to WebMD saying “nearly 50,000 Americans die of heart disease each year due to low intake of vegetable oils.”20

Mozaffarian has historically been a champion for healthy fats, even telling Forbes last year that, “Placing limits on total fat intake has no basis in science and leads to all sorts of wrong industry and consumer decisions.”21However, he is seriously misguided in recommending vegetables oils as a healthy fat. First, let’s be clear that this study did not prove cause-and-effect.

The incredible irony of this study and its fatally flawed recommendations is that they are indeed correct about the impact of optimizing fat intake but their ignorance of mitochondrial molecular biology has blinded them to the truth. The study’s recommendations will result in unmitigated health disasters for those who implement their foolish advice.

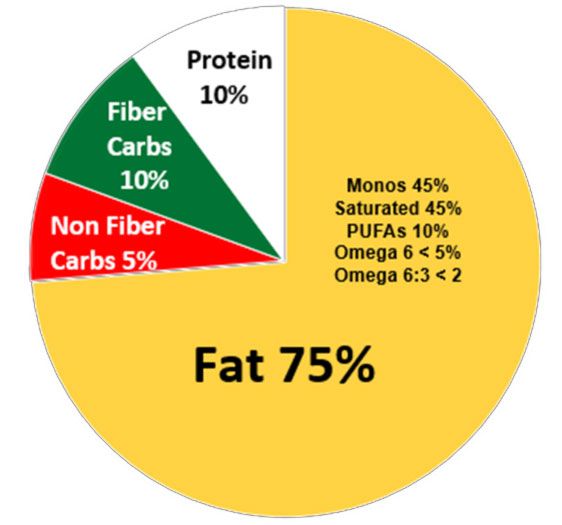

The healthy reality is that you do not exceed 5 percent of your calories as omega-6 fats and when you combine omega 3-fats the total should not exceed 10 percent. The omega 6:3 ratio should be below 2. The other 90 percent of your fat calories are split between monounsaturated fats like avocados, olives and macadamia nuts, and saturated fats. Ideally you should have more monos than saturates.

If you exceed more than 10 percent of your diet at PUFAs you will increase the concentration in the inner mitochondrial membrane and make it far more susceptible to oxidative damage from the reactive oxygen species generated there.

From my review of the molecular biology required to optimize mitochondrial function, it is best to seek to have about 75 percent of your total calories as fat. That leaves approximately 10 percent of your calories as protein and 15 percent as carbs which should be twice as many fiber carbs as non-fiber carbs, like vegetables, seeds and nuts.

The graph below is generated from data that represents my food selection for the last two weeks. I collected the data with the best nutrient tracker on the market which is Cronometer.com and is absolutely free.

Why Refined PUFAs (Vegetable Oils) Are so Bad for Your Health

I believe the widespread consumption of refined vegetable oil was largely responsible for the epidemic of chronic disease in the 20th century. Sugar clearly exacerbated this trend but I strongly believe the primary culprit was the implementation of the industrial processing of oil. The myth that vegetable oils (rich in omega-6 fats) are healthier for you than saturated animal fats has been a tough one to dismantle. But the truth cannot be hidden forever.

According to investigative journalist Teicholz, the increase in the amount of vegetable oils we eat is the single biggest increase in any kind of food nutrient over the course of the 20th century.

By one calculation, we now eat more than 100,000 times more vegetable oils than we did at the beginning of the century, when the consumption of processed vegetable oils was virtually nonexistent. Now, they make up about 7 percent to 8 percent of all calories consumed by the American public.

Vegetable oils are problematic for a number of reasons. The increased consumption of industrially-refined vegetable oils has led to a severely lopsided fatty acid composition, for instance, as these oils provide high amounts of omega-6 fats. The ideal ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fats is less than 1:2, but certainly less than 1:5, but the typical Western diet is now between 1:20 and 1:50.

Eating too much damaged omega-6 fat and too little omega-3 sets the stage for nearly all chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, depression, Alzheimer’s, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes, just to name a few. To correct this imbalance, you typically need to do two things:

- Significantly decrease omega-6 by avoiding processed foods and foods cooked at high temperatures Avoid using any industrially refined vegetable oils. The only exception would be coconut oil and MCT oil. Most olive oils are problematic as revealed by a recent 60 Minutes investigation that shows most olive oils are adulterated with cheap industrially processed vegetable oils.

- Increase your intake of heart-healthy animal-based omega-3 fats, such as krill oil

Vegetable Oils Are Highly Unstable and Easily Oxidized

There’s also the issue of glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup herbicide) contamination and genetic engineering that make vegetable oils of today even more hazardous than the earlier varieties (most vegetable oil comes from GE crops).

But even from the very beginning, vegetable oils were unstable. When heated, especially to high temperatures, they degrade into oxidation products. More than 100 dangerous oxidation products have been found in a single piece of chicken fried in vegetable oils, according to Teicholz.

So, while synthetic trans fats are being recognized as harmful and are in the process of being completely eliminated, we’re still faced with a huge problem, because restaurants and food service operations are reverting back to using regular vegetable oils (such as peanut, corn, and soy oil) for frying. But these oils still have the worrisome problem of degrading into toxic oxidation products when heated.

Replacing Saturated Fat With Refined Vegetable Oils Will Increase Your Heart Disease Risk

Replacing saturated animal fats with industrially processed omega-6 vegetable fats is linked to an increased risk of death among patients with heart disease, according to a BMJ study published in 2013.22 The study was an in-depth evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Heart Study and an updated meta-analysis.

The Sydney Diet Heart Study was a randomized controlled trial conducted from 1966 to 1973. Again this is absolutely no surprise and what one would predict if they understood mitochondrial metabolism. Researchers from the U.S. and Australia recovered the original data and, using modern statistical methods, they were able to compare the death rates from coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality.

The analysis included 458 men with a history of heart problems who were divided into two groups. One group reduced saturated fats to less than 10 percent of their energy intake and increased omega-6 fats (in this case omega-6 linoleic acid) from safflower oils to 15 percent of their energy intake. The control group continued to eat whatever they wanted. After 39 months:

- The omega-6 linoleic acid group had a 17 percent higher risk of dying from heart disease during the study period, compared with 11 percent among the control group

- The omega-6 group also had a higher risk of all-cause mortality

Foods that are naturally rich in saturated fats, like grass-fed meats, grass-fed butter, pastured eggs and coconuts, come in a near-perfect package, as they are typically loaded with healthy, fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E and K. Industrially processed vegetable oils, on the other hand, are highly processed and offer little nutritional value other than empty calories. More importantly they damage your cellular and mitochondrial membranes.

Another Major Concern With Your Oils

It’s becoming increasingly clear that a large percentage of the chronic disease present in Western nations is due to the introduction of refined vegetable oils. Prior to 1900 the average intake of vegetable oils was less than 1 pound a year, but in 2000 that had increased to 75 pounds per year. We simply never had the ability to consume this much vegetable oil prior to food processing. Refined oil has contributed to massive distortions in omega-3:6 ratios.

It is not that the naturally occurring non-refined omega-6 oils present in seeds and nuts are toxic; they are important nutrients for health. I personally consume about 10 to 15 grams of omega-6 oils a day, but not one microgram is refined as they are primarily in the form of seeds and nuts. I also eat about 4 ounces of clean fish a day in the form of wild Alaskan salmon, sardines, or anchovies, which provides about 9 to 13 grams of omega-3 per day for a 3:6 ratio of about 1:1.2.

Saturated Fats Are the Best Oils to Cook With

Tallow is a hard fat that comes from cows. Lard is a hard fat that comes from pigs. They’re both animal fats, and used to be the main fats used in cooking. One of their benefits is that, because they’re primarily saturated fats, they oxidize very little when heated. Since saturated fats do not have double bonds that can react with oxygen; therefore they cannot form dangerous aldehydes or other toxic oxidation products.

Saturated fats including lard, tallow and butter are therefore the preferred oils for cooking, but if you prefer a plant-based option, be aware that there are very healthy saturated plant fats as well — coconut oil and palm oil, specifically. Coconut oil is one of the healthiest fats you can eat, as it contains about 66 percent medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs).

MCTs are fats that are not processed by your body in the same manner as long-chain triglycerides. Normally, a fat taken into your body must be mixed with bile released from your gallbladder before it can be broken down in your digestive system. But, medium-chain triglycerides go directly to your liver, which naturally converts the oil into ketones (unless you are on a statin drug, which blocks the liver from converting them to ketones), bypassing the bile entirely.

Your liver then immediately releases the ketones, which are water soluble, into your bloodstream where they are transported to your brain to be readily used as fuel. Additionally they do not require L-carnitine to shuttle them into the mitochondria for fuel. There’s strong evidence suggesting that ketones actually help restore and renew neurons and nerve function in your brain and are an important treatment for neurodegenerative diseases.

Many People Need to Eat More Saturated Fats and Less Vegetable Oils

Most of us need to radically increase the healthy fat in our diet. This includes not only saturated fat but also monounsaturated fats (from avocados and nuts) and omega-3 fats. The research has spelled it out loud and clear that saturated fats are beneficial for human health.

Remember that you do not want to consume more than 10 percent of your total calories or fat calories as PUFAs (omega-6 plus omega-3 fats) as they will damage your cellular and mitochondrial membranes.

A 2014 meta-analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine used data from nearly 80 studies and more than a half-million people.23 It found those who consume higher amounts of saturated fat have no more heart disease than those who consume less. They also did not find less heart disease among those eating higher amounts of unsaturated fat, including both olive oil and corn oil.24

A 2015 meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) also found no association between high levels of saturated fat in the diet and heart disease. Nor did they find an association between saturated fat consumption and other life-threatening diseases like stroke or type 2 diabetes.25

Yet another meta-analysis, this one published in 2010, pooled data from 21 studies and included nearly 348,000 adults. It also found no difference in the risks of heart disease and stroke between people with the lowest and highest intakes of saturated fat.26 Indeed, far from posing a risk, it’s known that saturated fats provide a number of important health benefits, including the following:

- Providing building blocks for cell membranes, hormones, and hormone-like substances

- Conversion of carotene into vitamin A

- Optimal fuel for your brain

- Mineral absorption, such as calcium

- Helping to lower cholesterol levels (palmitic and stearic acids)

- Provides satiety

- Carriers for important fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K

- Acts as antiviral agent (caprylic acid)

- Modulates genetic regulation and helps prevent cancer (butyric acid)

If this sounds like a lot to remember, just remember this: mounting scientific evidence supports saturated fat as a necessary part of a heart-healthy diet and firmly debunks the myth that saturated fat promotes heart disease. For optimal health, eat real food — this means plenty of saturated fats and little to no refined fats, especially refined vegetable oils.

In Summary, Saturated Fats Are Healthy

Saturated fats:

- Increase your LDL levels, but they increase the large fluffy particles that are not associated with an increased risk of heart disease

- Increase your HDL levels. This more than compensates for any increase in LDL

- Do NOT cause heart disease as made clear in all the above-referenced studies

- Do not damage as easily as other fats because they do not have any double bonds that can be damaged through oxidation

- Serve to fuel mitochondria and produce far less damaging free radicals than carbs

- 1, 14 BMJ 2013;347:f6340

- 2 Nutrition. 1997 Mar;13(3):250-2; discussion 249, 253.

- 3 TIME May 13, 2014

- 4 BMJ 2015;351:h4962

- 5 Bull N Y Acad Med. 1968 Aug; 44(8): 1012–1020.

- 6 Circulation. 1969; 40: II-1-II-63

- 7 Arteriosclerosis. 1989 Jan-Feb;9(1):129-35.

- 8 Int J Epidemiol. 1979 Jun;8(2):99-118.

- 9 The Lancet September 28, 1968, Volume 292, No. 7570, p693-700

- 10 ClinicalTrials.gov October 27, 1999

- 11 JAMA. 1988;260(13):1917-1921

- 12 Am J Clin Nutr May 1998 vol. 67 no. 5 828-836

- 13 Authority Nutrition December 2015

- 15 Am J Clin Nutr March 2010 vol. 91 no. 3 502-509

- 16 Weston A Price January 13, 2015

- 17, 18 Open Heart 2015;2: doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000196

- 19 Journal of the American Heart Association January 20, 2016

- 20 WebMD January 20, 2016

- 21 Forbes June 24, 2015

- 22 BMJ 2013;346:e8707 [Epub ahead of print]

- 23, 24 Annals of Internal Medicine March 18, 2014

- 25, 26 BMJ 2015;351:h3978

Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer

Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits

Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives

How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth

New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth New Study Confirms Health Benefits of Coconut Oil and USDA False Claims Against It

New Study Confirms Health Benefits of Coconut Oil and USDA False Claims Against It

Leave a Reply