By Alliance for Natural Health

The American Heart Association’s woefully outdated dietary guidelines are hurting Americans’ health.

Last December, we told you about the American Heart Association’s (AHA) new new cholesterol guidelines that would make 33 million healthy Americans dependent on statins. These are the most widely prescribed class of drugs in the world—drugs so dangerous that the FDA mandates their side effects be disclosed in labeling.

The AHA’s statin guidelines are based on the outdated, simplistic notion that there are two kinds of cholesterol: “bad” (LDL) and “good” (HDL). Moreover, the AHA’s dietary guidelines are also centered on the notion that “bad” cholesterol causes heart disease, and that since saturated fat may raise “bad” cholesterol levels, it’s the ultimate dietary evildoer.

The problem with AHA’s “logic?” Not only has this bad/good cholesterol dichotomy been solidly debunked by study after study—it was never proven in the first place. According to the Wall Street Journal, the notion that saturated fats and LDL clog our arteries came from a “derailment” of nutrition policy “by a mixture of personal ambition, bad science, politics, and bias.”

Below, in bold, are some other highlights of AHA’s dietary guidelines, accompanied by why they actually are bad for your heart:

- “Reduce saturated fat!” Wrong. In fact, eliminating saturated fat from the modern diet might be harmful, if only because of the alternatives that replace sources of saturated fat. Take butter, for example. Raw, organic butter from grass-fed cows can be extremely healthful: it contains vitamin A in its most bioavailable form, lauric acid, antioxidants, vitamin E, and vitamin K2. But the alternatives to butter—margarine and hydrogenated or processed polyunsaturated oils—are far more detrimental to your health than saturated fat. They are actually a leading cause of heart disease. Recently, the evidence that saturated fat has noconnection to heart disease has been snowballing. To give just one example: as reported by LewRockwell.com, a massive meta-analysis by the British Heart Foundation (it examined seventy-two academic studies involving over 600,000 participants) found that saturated fat consumption was not associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

- “Drink low-fat and skim milk!” Wrong. A recent study has shown that children who drink whole milk are slimmer than kids who drink skim! One theory for this is that “full fat foods” promote satiety. Additionally, full-fat dairy can actually reduce your risk of heart disease, as well as diabetes and cancer. (Not surprisingly, the AHA doesn’t even discuss raw milk and its proven benefits.)

- “Avoid ‘bad’ cholesterol!” LDL has some crucial health benefits—it can even provide protection from cancer as well as support aging muscle mass. In addition, studies show that lower levels of LDL don’t necessarily lessen your risk of heart disease.

- “Limit Your Intake of Red Meat!” Wrong again! Unless you have prostate cancer or a propensity to it and want to be extra cautious, there are reasons to view hormone-free, grass-fed beef positively. Red meat is an excellent source of protein and other nutrients. Among other nutrients, it contains L-carnitine, an amino acid that is helpful for heart disease. A large meta-analysis, published in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings, found that L-carnitine actually helps heal the heart after a myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- “Don’t smoke tobacco, and avoid secondhand smoke!” Finally—something we can all agree on.

Meanwhile, statin drugs may actually be driving Americans to overeat: a twelve-year study published in JAMA Internal Medicine found that statin users increased their calorie intake by 9%, and fat consumption by 14.4%, over the study period (those who didn’t take statins didn’t significantly change in either measure).

This study controlled for age, race, education, diabetes, and high cholesterol—which means that researchers isolated statin drugs as the reason participants were overeating. Researchers speculate that the explanation is psychological: those on a “magic pill” feel entitled to take greater liberties with their diet.

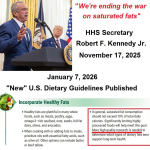

HHS Secretary Kennedy Breaks His Promise: "War on Saturated Fat" Kept in Tact with New U.S. Dietary Guidelines

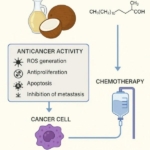

HHS Secretary Kennedy Breaks His Promise: "War on Saturated Fat" Kept in Tact with New U.S. Dietary Guidelines Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer

Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits

Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives

How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth

New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth