Diet and Disease: Not What You Think

by Sally Fallon and Mary G. Enig, Ph.D.

Heart disease is America’s major killer; it’s prevention is our most urgent public health priority. Americans must change their diet, say the experts. Steer clear of traditional foods like butter, cream, cheese, eggs, and meat, they tell us. Rich foods contain cholesterol and saturated fats — “artery clogging substances.”

The accumulation of hardened plaque in the arteries, or atherosclerosis, is indeed a major cause of heart disease in Western nations.

The accepted explanation for its prevalence in civilized countries is the lipid hypothesis, namely that dietary saturated fat and cholesterol lead to elevated levels of cholesterol in the blood, and that these elevated levels of cholesterol cause the pathogenic atheromas that block blood vessels.

This theory has been promoted by the American Heart Association since the mid-1960s. It forms the basis of governmental nutritional recommendations, which in turn have spurred consumer acceptance of a vast array of low-fat, cholesterol free food products, most of which contain ingredients that are new to the American diet.

Numerous studies, both national and international, have explored the lipid hypothesis — and consumed the lion’s share of research dollars in this area — including three major projects funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, a division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The first and best known of these studies was the Framingham Heart Study, carried out in the town of Framingham, Massachusetts.

Although Framingham is often associated with proof of the lipid hypothesis, the results of this 40-year study have been a disappointment to its promoters.

Investigators claimed that there was a 240% increase in “risk” of coronary heart disease, or CHD, between cholesterol levels of 182 and 244. But the actual rate of increase was only .13%.

Between cholesterol levels of 244 and 294, the rate of CHD actually declined.

Thus Framingham investigators found virtually no difference in heart disease for serum cholesterol levels between 182 and 284 the vast majority of the U.S. population.

Nor did they find that diets high in fat and cholesterol predisposed an individual to heart disease.

As Dr. William Castelli, the current director of the Framingham project, admitted as recently as 1992:”In Framingham, Massachusetts, the more saturated fat one ate, the more cholesterol one ate, the more lories one ate, the lower people’s serum cholesterol… we found that the people who ate the most cholesterol, ate the most saturated fat, ate the most calories weighed the least and were the most physically active.”

The second government-funded study was the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) for 362,000 men.

Researchers found that annual heart disease deaths increased from about 1 per 1,000 for cholesterol levels of 180 to slightly less than 2 per 1,000 for cholesterol levels of 300 — a 100% increase in “risk” but a trivial increase in rate of less that .1%.

A more significant finding was an increase in total deaths for cholesterol levels below 160.

The final major NIH study was the Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial (LRC), a project that cost $150 million and received intense media attention.

All subjects in the trial were put on a low-cholesterol, low-saturated fat diet. One group received a cholesterol lowering drug, the other a placebo. Average cholesterol reduction for the drug group was 8.6% which had, according to researchers, a 17% reduction in rate of heart disease.

This led to the oft repeated statement: “For each 1% reduction in cholesterol, we can expect a 2% reduction in CHD events.” But when independent researchers tallied the LRC data, they found no difference in CHD between the two groups. An unequivocal but rarely published finding of the LRC was an increase in deaths from cancer, intestinal disease, stroke, violence, and suicide in the group taking the cholesterol-lowering drug.

Both the popular press and medical journals portrayed the LRC as the long-sought proof that animal fats and dietary cholesterol are the cause of heart disease. The 1984 government-sponsored Cholesterol Consensus Conference called for mass cholesterol screening and defined all Americans with cholesterol levels over 200 as “at risk.”

Participating scientists recommended the prudent diet for “at risk” Americans, one low in saturated fat and cholesterol. A specific recommendation was the replacement of butter with margarine. The ensuing National Cholesterol Education Program instructed American physicians in techniques for lowering serum cholesterol through diet ant drugs.

The estimated current cost for cholesterol screening and treatment in the United States now exceeds $60 billion annually.

The application of a modicum of common sense could have prevented the massive expenditures lavished on the lipid hypothesis during the past 30 years.

The lipid hypothesis implies that animal fat consumption must have increased significantly since 1920 to correlate with the rise in heart disease, but in fact the consumption of saturated animal fats in America declined steadily during that period, while use of vegetable fats increased dramatically.

Autopsy studies of vegetarians reveal that although they have lower serum cholesterol values than non-vegetarians, they have as much atherosclerosis as non-vegetarians.

In fact, the International Atherosclerosis Project, which analyzed 31,000 autopsies from l5 countries, found no correlation between animal fat intake and degree of atherosclerosis or serum cholesterol level.

Michael DeBakey, the famous heart surgeon, surveyed 1,700 patients with atherosclerosis and found no relation between levels of serum cholesterol and degree of hardening of the arteries. Other U.S. studies — the Veterans Clinical Trial, the Minnesota State Hospital Trial, the Honolulu Heart Program, and the Puerto Rico Heart Health Study — found no significant relation between a diet high in cholesterol and saturated fats with CHD.

Unfortunately, these studies do not receive front page coverage in American newspapers, and dissenting voices must content themselves with publication in obscure medical journals. One of these voices is the eminent researcher Dr. George Mann, who states categorically:

“The diet-heart hypothesis has been repeatedly shown to be wrong, ant yet, for complicated reasons of pride, profit, and prejudice, the hypothesis continues to be exploited by scientists, fund-raising enterprises, food companies, and even governmental agencies. The public is being deceived by the greatest health scam of the century.”

Michael Gurr, Ph.D., renowned expert on lipids and author of the authoritative textbook on lipid biochemistry, recently stated that “whatever causes coronary heart disease, it is not primarily a high intake of saturated fat.” He criticized “…the degree of self delusion in research workers wedded to a particular hypothesis despite the contrary evidence!”

So if it ain’t saturated fats ant cholesterol, what causes heart disease? There are, in fact, a number of dissenting theories, most of which dovetail into a compelling list of dietary and lifestyle factors that are unique to civilized societies. Consider the following:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heart Disease Has Many Forms

What emerges is a clear association of heart disease with the increased consumption of devitalized, processed, fabricated food items, including sugar and fructose, pasteurized milk, soft drinks, fortified white flour, miller and egg powders, caffeine, imitation broth products, synthetic vitamins, vegetable oils, and hydrogenated fats.

The lipid hypothesis not only clouds this picture, but inhibits necessary research that could illuminate these connections more clearly. Instead of adding to medical and nutritional understanding, it may be undermining public health — promoting the substitution of newfangled, altered, imitation products for nourishing traditional whole foods, including butter, cream, cheese, eggs, and meat.

Although not unknown, heart disease was relatively rare at the turn of the century, accounting for approximately 8% of all deaths in the United States.

Today coronary heart disease, or CHD, accounts for about 45% of all deaths.

Incidence of heart disease rose precipitously between 1920 and 1960. Since that time, mortality rates from CHD have declined somewhat. This means that victims of heart disease are living longer, due most likely to improved surgical techniques and the advent of angioplasty; but morbidity rates — the incidence of heart disease — continue to rise, although at a lower rate than before.

Of greatest concern is the high rate of heart disease in American men between the ages of 45 to 65.

Heart disease is not a single malady, but a complex of disease coming under a single rubric.

Damage to the heart muscle or myocardium may be due to a congenital defect, or result from inflammation and damage associated with any number of viral, bacterial, fungal, rickettsial or parasitic diseases; from rheumatic fever or syphilis; from toxic chemicals such as carbon monoxide or drugs; from auto-immune reactions or genetic disorders in which important cellular proteins in the heart muscle are deranged; or from disruption of enzymes affecting cardiac function.

The heart may also be damaged by an imbalance between the blood supply and the demands of the heart muscle leading to ischemia, a local deficiency of blood supply, and infarction, the death of an area of heart tissue.

Such deficiency may be caused by physical exertion or emotional trauma, increasing the heart’s need for blood; or from a drop in blood supply due to excess bleeding, a spasm in an artery, a blood clot (thrombus) or by coronary artery disease, a condition in which the arteries become gradually blocked by the buildup of abnormal plaque (atheromas) and hardened through calcification. Blockage often occurs in the large arteries feeding the heart (the coronary arteries), or in those supplying the brain, increasing the risk of stroke.

In cases of moderate blockage of the coronary arteries, the patient may suffer from angina pectoris, bouts of brief chest pain; moderate blockage combined with increased demands on the heart, due to exertion or trauma; or severe blockage due to arterial plaque, a clot, a spasm, or any combination of these, may lead to a myocardial infarction, the dreaded heart attack, resulting in cardiac dysfunction and often rapid death. Sudden death is often triggered by an acute arrhythmia — disruption in the rhythms of the heart beat — during a heart attack.

While coronary artery disease is a common cause of heart attack, myocardial infarction may also occur in the absence of arterial blockage, due to a spasm, clot or organic failure of the heart muscle.

Heart disease due to syphilis and infectious disease has been around a long time and probably accounts for a good portion of CHD deaths before 1920. Fatty streaks, lesions, and plaque in the arteries are found in many primitive people, but coronary artery disease, the pathological buildup of hardened plaque leading to partial or total occlusion of major arteries, seems to be a disease of civilization, and probably accounts for a great deal — though not all — of the increase in heart disease between 1920 and 1960, and its continued menace to the present day.

Sally Fallon is the author of Nourishing Traditions: The Cookbook that Challenges Politically Correct Nutrition and the Diet Dictocrats (NewTrends Publishing 877-707-1776) and Mary G. Enig, Ph.D. is the author ofKnow Your Fats: The Complete Primer for Understanding the Chemistry of Fats, Oils and Cholesterol(Bethesda Press 301-680-8600).

Reprinted with the permission of the authors.

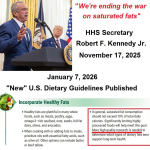

HHS Secretary Kennedy Breaks His Promise: "War on Saturated Fat" Kept in Tact with New U.S. Dietary Guidelines

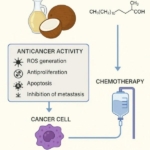

HHS Secretary Kennedy Breaks His Promise: "War on Saturated Fat" Kept in Tact with New U.S. Dietary Guidelines Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer

Research Continues to Show Virgin Coconut Oil's Effectiveness in Treating Cancer Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits

Coconut Oil Continues to Benefit Alzheimer's Patients over Drugs as Studies Continue for Neurological Benefits How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives

How the Simple High-Fat Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Continues to Change People's Lives New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth

New Studies Continue to Show that Coconut Oil is the Best Oil for Treating Skin Conditions and Maintaining Healthy Skin and Teeth